Ice on Ceres

thermal and vapor transport models

Ceres is the largest body in the Main Asteroid Belt, and also the innermost dwarf planet in the solar system. At a mean solar distance of AU, Ceres also occupies a very interesting place, near the “snow line” – an important boundary in the protoplanetary disk, where water vapor transitions to ice. Ceres’ surface contains little water, because the snow line has moved outward to AU (near the orbit of Jupiter). However, sporadic water vapor detections around Ceres have led to the idea that remnants of the dwarf planet’s icy past might linger just beneath the surface.

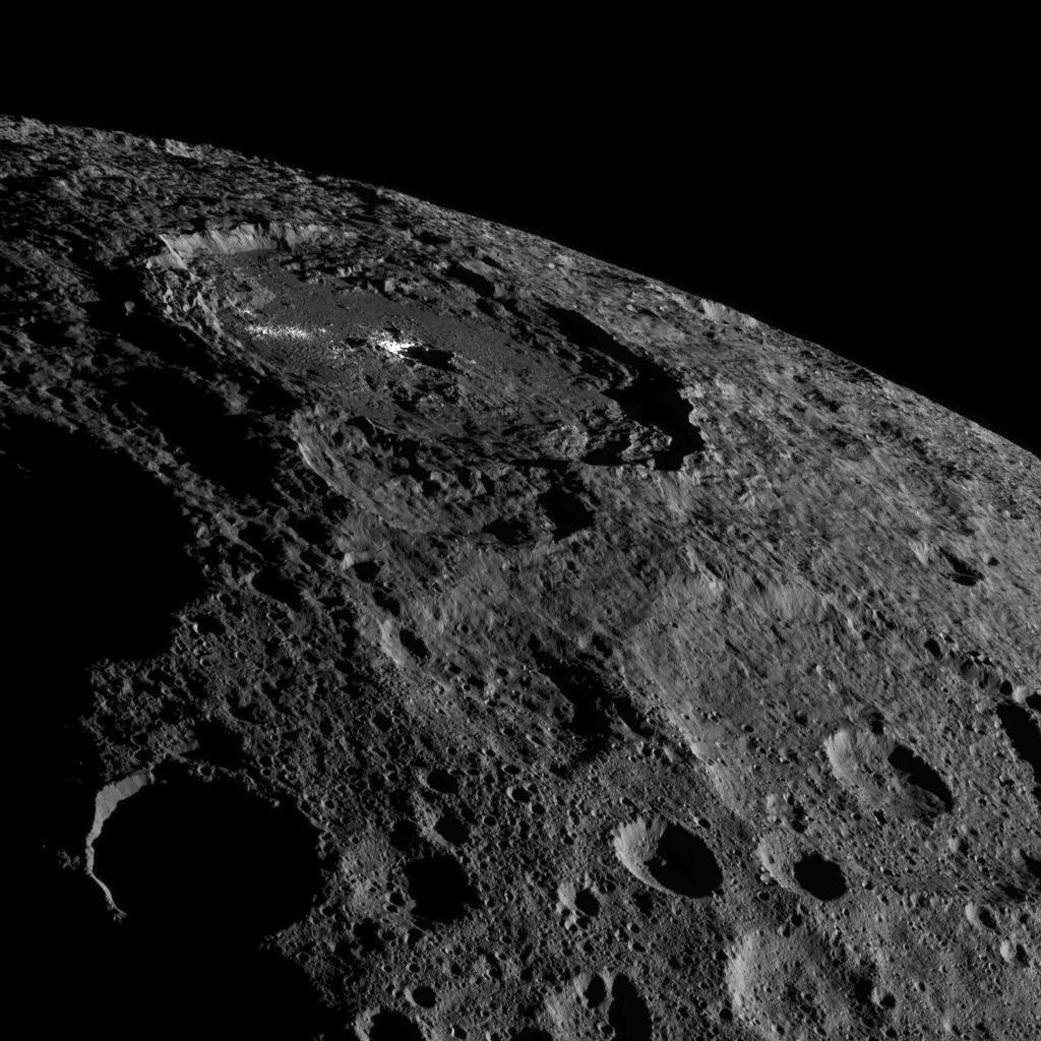

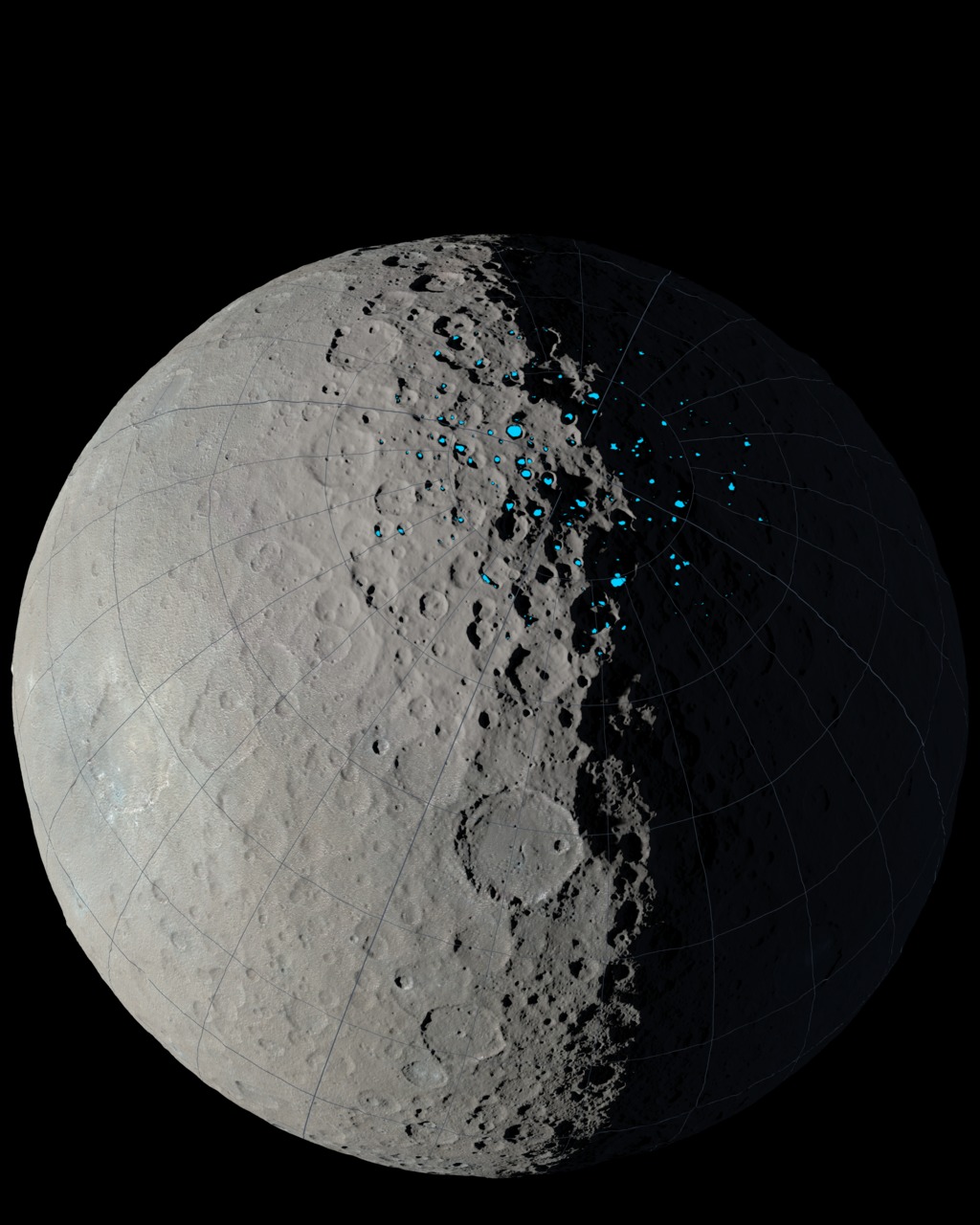

We developed thermal and vapor transport models to investigate ice stability on Ceres, using realistic rough topography. Accounting for roughness increases the modeled extent of ground ice (to latitude), but surface ice is limited to permanent shadows on billion-year timescales. However, lifetimes of illuminated ice may be up to kyr if it is relatively pure and cohesive. NASA’s Dawn mission found evidence for widespread ice in the near subsurface and exposed ice in the polar shadows of Ceres, confirming our model predictions.

Further information:

- Landis, M.E., ..., Hayne, P.O., et al., 2019. Water vapor contribution to Ceres' exosphere from observed surface ice and postulated ice‐exposing impacts. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, 124(1), pp.61-75. Link

- Hayne, P. O., & Aharonson, O. (2015). Thermal stability of ice on Ceres with rough topography. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, 120(9), 1567-1584. Link